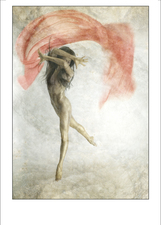

A Gum bichromate, is a photographic printing process invented in the early days of photography in 1839 by the Scottish chemist Mungo Ponton. It is capable of rendering painterly images from photographic negatives. No darkroom or enlarger is needed, but instead, a contact printing frame is used with an ultraviolet light source.

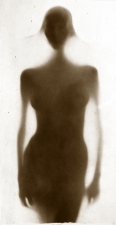

Nocturnes, arose from an invitation to shoot in Kiev in the spring of 2015. At first glance these sculptural photographs appear to be glossy mirror-like black boxes on the wall. As night falls or as the ambient light in their environment changes, a soft luminescence comes to life. Lyrical, almost balletic figures emerge whose movements are echoed in the gesture of the carbon sheath that obscures them by day.

Initially, viewers can’t be sure if what they’re seeing is the print itself or a ghost-like latent image. Like a retinal image produced after staring at the sun, the ghost lingers behind its frame - sometimes visible and sometimes sliding across the edges of our vision.

This new work draws inspiration from the recent invention of Graphene, a substance with the potential to revolutionize the world of technology. This material is currently a theory yet to be realized in physical form. Booth’s new images parallel that paradoxical and alluring mystery.

Initially, viewers can’t be sure if what they’re seeing is the print itself or a ghost-like latent image. Like a retinal image produced after staring at the sun, the ghost lingers behind its frame - sometimes visible and sometimes sliding across the edges of our vision.

This new work draws inspiration from the recent invention of Graphene, a substance with the potential to revolutionize the world of technology. This material is currently a theory yet to be realized in physical form. Booth’s new images parallel that paradoxical and alluring mystery.

The work collected in the Come To Your Senses series represents Booth’s first major foray into sculpture. Using casting, an imprint can be taken directly from the body rather than translating it through light, chemicals, or pixels as a photograph does. Silicone, rubber, LEDs, computer parts and even custom fragrances bring the tradition of casting up to date. The directness of casting heightens the graphic nature of disembodied and collaged body parts, and somehow, also renders them more blithely amusing. A funniness that seems appropriate as his work adopts a turn toward an increasingly lighthearted maturity.

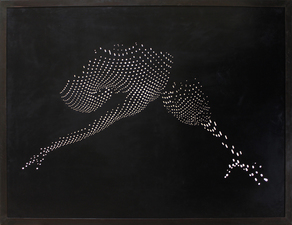

Early transitional pieces like Digital Print, a grand finale drawn from a humble pun, points at questions of the nature of photography today and proves the enduring allure of physical forms in this digital-centric world. Battery Low uses over 2000 hearing aid batteries (Booth’s own) hand studded onto plexiglas to transfigure a body into a photograph and then back again into the sculptural realm. In this way the image is, by design, also understandable to someone who cannot see. A uniting quality of this body of work is its exploration of heightened sensation. Sextet an anatomical study in six parts is accompanied by custom made fragrances applied to each piece. Most of the sculptures are intended to be felt, not just seen. Booth’s growing interest in amplified senses, is at once an investigation of an implied loss of sensation, and an act of cross-modal neuroplasticity.

Pieces like Lustre and Nombrilism prompt us to daydream of an alternate world, perhaps inside of Booths head, where the bodily bits and bobs he uses in his seats, lamps, cakes, and computers take over as the building blocks of whole environments. Of course, the form of the objects we live with is already inextricably inspired by human anatomy. The furniture we sit on is a reflection of the shape and mass of our bodies, the food we eat and utensils we eat with are designed to the specifications of the mouth, even the way we caress our phones says something about our intimate relationship with the objects around us, whose origin is often ergonomic and imitative of the human form. We even lend them anthropomorphic names, the legs of a table, the arms of a candelabra, the spine of a book, the tongue of a shoe and even the butt of a cigarette. The shape and the language of objects is so often derivative of our own anatomy. Booth’s sculptures, created by the partitioning, multiplication and reconstruction of the human body gratifyingly brings this relationship full circle.

Early transitional pieces like Digital Print, a grand finale drawn from a humble pun, points at questions of the nature of photography today and proves the enduring allure of physical forms in this digital-centric world. Battery Low uses over 2000 hearing aid batteries (Booth’s own) hand studded onto plexiglas to transfigure a body into a photograph and then back again into the sculptural realm. In this way the image is, by design, also understandable to someone who cannot see. A uniting quality of this body of work is its exploration of heightened sensation. Sextet an anatomical study in six parts is accompanied by custom made fragrances applied to each piece. Most of the sculptures are intended to be felt, not just seen. Booth’s growing interest in amplified senses, is at once an investigation of an implied loss of sensation, and an act of cross-modal neuroplasticity.

Pieces like Lustre and Nombrilism prompt us to daydream of an alternate world, perhaps inside of Booths head, where the bodily bits and bobs he uses in his seats, lamps, cakes, and computers take over as the building blocks of whole environments. Of course, the form of the objects we live with is already inextricably inspired by human anatomy. The furniture we sit on is a reflection of the shape and mass of our bodies, the food we eat and utensils we eat with are designed to the specifications of the mouth, even the way we caress our phones says something about our intimate relationship with the objects around us, whose origin is often ergonomic and imitative of the human form. We even lend them anthropomorphic names, the legs of a table, the arms of a candelabra, the spine of a book, the tongue of a shoe and even the butt of a cigarette. The shape and the language of objects is so often derivative of our own anatomy. Booth’s sculptures, created by the partitioning, multiplication and reconstruction of the human body gratifyingly brings this relationship full circle.

Sinuous nudes drift lyrically upwards, caught mid-flight in an enveloping dark column. The delicate scale of these lithe figures compared to the vastness of their frame is a considerable shift from Booth’s previously snug outlining. In Volari the figures cut free of any kind of constriction, freed even of gravity, they are trapped only in time, suspended in the zenith of their leap.

In Lacuna, the classical constructs of a photograph are turned inside out. The essence of what photography is, the act of capturing light, is inverted. Hand punched holes that make up the matrix of the pictures surface emanate their own light, a light contained within the framed picture. Industrial materials, massive sheets of black rubber, plexiglas, LEDs and thick patinated frames are finessed into emotive, pointillistic images of the body. Oversized pixels nod to contemporary technology, but are conversely and staunchly hand crafted. The imposing larger-than-life sized figures are half enveloped riddle-like in shadow, often rendering their contorted poses enigmatic.

The images that comprise the Anamorphosis series are constructed of bodies fragmented, foreshortened and multiplied. The resulting kaleidoscopic fractals are both deeply romantic and archly mathematical. Independent limbs and torsos are the ingredients of geometric explosions, creating potent figurative abstractions, almost vortographic of a corporal flavor. The soft organic quality of the body is preserved even in the most architectural iterations, possibly by some magic of Booth’s unorthodox treatment of the gelatin silver process. The effect is rapturously dreamlike. Soft illuminated lines and sharp turns dissipate into eternity. The amorphous body becomes a vocabulary, building a story that is played out in isolation from our reality, without gravity, as if caught in a hypnogogic state.

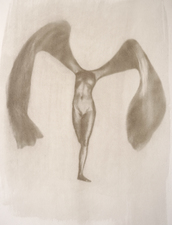

The images in Osmosis are imaginations of form as stylized as charcoal drawings. Figures constructed of shadow, blended and erased, create a rich depth that stretches across the picture plane but refrains from extending backwards into it. Perspective is compressed, and the body, a substrate acted upon by light, is at times illuminated to the point of being consumed or bleached into a tranquilly pale background. Tender mid-tones articulate areas that softly blend into each other, unconstrained by borders. Gesture triumphs over detail to tangible effect, expressing a body we know by impression if not by name.

Long, powerful female nudes take center stage in Ova, a collection that turns its focus to a more contemporary vision of femininity. Sinuous ovals frame the arc of bodies illuminated by an overlay of a patterned mesh, tangles of line and palimpsest text. The egg shape that encloses them suggests some kind of gestation, but the comfortable sex appeal they display in their incubation feels strikingly independent. Their stance lacks any of the self-consciousness associated with nudes of the male gaze tradition. If anything, one feels that finally a laudable audience and motive has been found for their seduction.

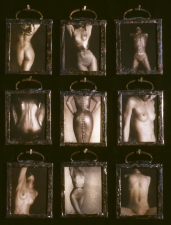

A cornucopia of pocket sized gelatin silver photographs housed in coarse metal frames depict an equivalent range of intimate scenes, some sweet, some sultry. The personal scale feels fitting for the tender romantic pictures as well as the darker visions of cloistered fascination. When tiled, these snapshots form a larger artwork, permutations of which illuminate a grander scheme. Simple gestures become overarching lines, and bodies begin to imply a geometry that later becomes a major motif of Booth’s work.

A delicate blending of tones ranging from straight black and white to a warm oxblood sepia gesturally sketch powerful bodies both female and male. The tones harken back to the very early days of photography but the poses are reminiscent of an even more distant history, that of classical sculpture. Booth creates a palpable surfacing both on the skin of the model and the surface of the photograph itself. He relies on and revels in the mutations and mistakes created by the chemical processing of the photographs. The figures are only elucidated by the subtle means of chiaroscuro, a kind of blending where darkness evolves softly and seamlessly into legible form.

These intimate, eye sized portraits invite the viewer to step into an erotic tableau. The photographs, designed to be seen one at a time, transform us into the voyeur at the keyhole. The image is conveyed directly from paper to brain, like a daydream. The private nature of this relationship is heightened by the erotically charged scenes portrayed. The glossy metallic surface of the skin is pulled, wrapped and bound in cord. Bodies are both caressed and compressed, pulled and modified, creating a new vision of beauty that gives a nod to shibari but alludes to inclinations much more basic.

These pictures live in that rare moment where titillation and slapstick cross-pollinate. Male and female protuberances are treated with equal flippancy and given their own individual characterizations that throw conventional roles to the wind. Suddenly an index finger holds power over a penis. With traditional dominances erased, the weight of sexual politics is removed and leaves only the curiosity of playful possibility.